Speaking the Gender of God

- Lily Potito

- Nov 6, 2020

- 26 min read

Gender issues weren't the hot topic when I wrote this four years ago. But Speaking the Gender of God has nothing to do with how each of us identifies. It's about the mystery that is God.

Written for Dr. Michael Dauphinais' Triune God class, November 6, 2020

Welcome to our continuing series of Theology on Tap. Today we are going to discuss Sister Elizabeth Johnson’s position on our male image of God, particularly as set forth in Chapter 6 of her1998 work, She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse.

Elizabeth Johnson, CSJ, a well-known contemporary feminist Catholic theologian, recently retired from her position as Distinguished Professor of Theology at my own alma mater, Fordham University, is not without controversy. She has been praised by the Jesuit priest James Martin, yet criticized by the USCCB’s Committee on Doctrine. That Committee, reviewing her work Quest for the Living God, stated

“Sr. Johnson claims to be retrieving fundamental insights from patristic and medieval theology. As we have seen, however, this is misleading, since under the guise of criticizing modern theism she criticizes crucial aspects of patristic and medieval theology, aspects that have become central elements of the Catholic theological tradition confirmed by magisterial teaching...”[1]

Father Martin counters that criticism, calling Johnson “one of [his] favorite theologians”[2] and calling She Who Is:

“a remarkable and remarkably readable work on the often overlooked feminine imagery of God in the Bible (and elsewhere in our tradition), which opened my mind to new ways of thinking about God.”[3]

Tonight, I want to discuss this work, which received such widely disparate reactions, particularly in the light of the writing of St. Thomas Aquinas’ view on images of God as set forth in his Summa Theologica.

Johnson holds that Judeo-Christian depictions of God, in both word and image, have been limited to the view of God as masculine and patriarchal. God is shown as Father, not mother; as Lord, not Lady; as King, not Queen. All of these words are gender specific. We may state that God is beyond gender, but that is not reflected in how we speak of God or in our imagery of God. In She Who Is,

“Johnson critiques traditional speech about God, which derives ‘almost exclusively from the world of ruling men,’ as oppressive.”[4]

Having grown up in the same pre-feminist era as Elizabeth Johnson, I understand her distaste for the exclusive use of male language and imagery for God, but I do not join her in viewing it as oppressive. I think the Bible leads us to this usage, and I think Aquinas would agree, as he reminds us:

“It is written (Exod 15:3): The Lord is a man of war. Almighty is his name.”[5]

In Exodus and other books of the Bible, God reveals Himself in masculine terms, and specifically as Father. A priest I know explains it like this:

If we refer to God as mother rather than father, we are manipulating God’s own words. If we claim God revealed Himself in the Bible as a Father due to patriarchal cultural conditioning, but is actually something different, then we are stating we cannot trust the words of the Bible. If we cannot trust the Bible, the inspired word of God, we would have to say that God is a liar. [6]

I doubt any of us want to go on record as calling God a liar.

Referring to God with male pronouns and terms is in keeping with God’s own word, and his role as Father. In Matthew 6:9, Jesus taught us to pray to God using these words:

“Pray then like this: Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.”[7]

Jesus could have said “our creator, or “our parent,” or even “our mother.” If we instead call God “mother” or, following Johnson’s lead, “Sophia,” we would seem to be molding our own interpretation of God rather than recognizing that of the Bible.

Yet, even though God calls himself Father, we must also recognize that as the Creator, He created without assistance. In nature, the vast majority of species requires participation of both male and female to procreate. We were all created in God’s image:

“When God created man, he made him in the likeness of God. Male and female he created them, and he blessed them and named them Man when they were created.”[8]

This translation, at least, delineates a difference between being “Man” and being “male and female.” Since God created Man in His own image, and since He created Man as both male and female, “Man” must include both masculine and feminine, and God Himself must include both those qualities which make one male and those qualities which make one female.

We must then ask if, because God presents himself as Father in the Bible, must we see Him specifically as male? In ST I, Q1, A10, Aquinas asks “Whether in Holy Scripture a Word May Have Several Senses?”[9] In his response, Aquinas states:

“The author of Holy Writ is God, in whose power it is to signify his meaning, not by words only (as man also can do), but also by things themselves. . .. Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. Xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses.”[10]

Aquinas makes further reference to the image of God:

“it is absolutely true that God is not a body;”[11]

“it is impossible that matter should exist in God,”[12] and

“God is the same as his essence or nature.”[13]

Aquinas holds that since God is not a body but a Spirit, God is neither male nor female, and would likely concur that the use of masculine imagery is due to a limitation of language, not of theology. While language does change over time, we have not yet moved to a genderless version of English. While we now consider “humankind” to be more appropriate than “mankind,” mankind is still understood to include both genders. Although we commonly use words once considered male-gendered for both genders, as in actor and author; some terms have transformed, like mail carrier for the older mailman; still other terms, like waiter and waitress, have thus far maintained a dual vocabulary. Referring to God with male pronouns and terms is a matter of convention. In language, we tacitly agree that a term which ordinarily or historically meant only males may include both male and female, where an alternative genderless word cannot be easily used. I believe Aquinas understands this limitation of language, and would thus not insist that we consider God as male because of the words of the Bible

Aquinas tells us that God is not just perfect, but most perfect.[14] If God is most perfect, and yet also male, would women then be less perfect than God? But, as I said earlier, Genesis delineates Man as both male and female. God is most perfect, perfectly perfect, and Man reflects God’s perfection. When God separated Man into male and female at the creation of Eve, He did not make Eve of a different substance than Adam, but of the same substance. If Adam and Eve are of the same substance, how could Eve be less than Adam? Admittedly, humans need both male and female to create new life, and God, who is neither male nor female, begat through His own power. We call Him God, because God relates to His creation as a Father, that is, paternalistically. The essence of Fatherhood is the begetting of life. God is the origin of all life, both human and divine, and therefore God is called Father. God begets life, and in the begetting of life, God's relationship to what he begets is as Father. We can state both that God is a Father because He begets, and that God begets because God is a Father.

Aquinas wrote

“God is in all things...as an agent present to that upon it works....it must be that God is in all things, and innermostly.”[15]

And, a little later,

“spiritual things contain those things in which they are; as the soul contains the body. Hence...all things are in God, inasmuch as they are contained by Him.”[16]

All things are in God. How, then, can God be simply male or female?

Aquinas also states:

“The blessed see the essence of God,”[17] and

“the essence of God, however, cannot be seen by any created similitude representing the divine essence itself as it really is.”[18]

If using male terms for God had a relation to the essence of God, it would follow that we would then see God as he is. But Aquinas is clear:

“it is impossible for any created intelligence to comprehend God”[19]

Aquinas tells us that God

“can be named by us from creatures, yet not so that the name which signified Him expressed the divine essence in itself.”[20]

Aquinas further states

“we attribute to Him abstract names to signify His simplicity, and concrete names to signify His substance and perfection, although both these kinds of names fail to express His mode of being, forasmuch as our intellect does not know Him in this life as He is.”

I think Aquinas would be quite comfortable referring to God with male-gendered words, but would insist that we consider God neither as male nor female. Once we claim gender in some way defines God, we are by our language than forcing a limit on our depiction of God.

We use words to speak of God, for words are a primary mode of communication. So, we refer to God with masculine imagery, and masculine titles, even though we know that God is neither male nor female. The characteristics of gender (masculine or feminine) are how God creates in His image in the created physical sphere. Created reality reflects the invisible reality. Mankind bears God's image in their Spirit because men and women can reason, love, will, choose, and know. Human beings are self-aware; animals are not.

Johnson’s distaste for using male imagery and pronouns to speak of God brings her to choose to use female imagery instead. In She Who Is,

“Johnson critiques traditional speech about God, which derives ‘almost exclusively from the world of ruling men,’ as oppressive.”[21]

She offers examples from other cultures:

“Johnson’s examination of classical theology points out the richness of both tradition and the Bible in the multitude of symbols used for God. There are symbols taken from personal relationships, from human crafts, from philosophy, and from nonliving objects such as rocks. Many terms refer to the work of creation. African usage tends to honor God as ‘The One who. . ..’ Islamic tradition has ninety-nine names for God; the hundredth name is thought to be the true one that does not exist because God is ineffable. Names multiply because none of them can express the whole nature of God.”[22]

Johnson has also written that:

“God is positively misrepresented if any one image is thought to be adequate.”[23]

For her, this means that we ought to have both male and female images of God. However, I hold that we have a multitude of images of God, that even the sum of all those images does not come close to the reality of God, and that bringing gender into the imagery has a negative, rather than a positive, effect on our understanding of God. We can neither see nor understand God and must thus understand our limitations. Both our words and our images for God are analogical. Johnson concedes this is taught by Aquinas:

“According to Aquinas, whose various uses of analogy have kept generations of commentators busy, this threefold movement of analogy is clarified by contrast with two other possibilities, On the one hand, words about God are not univocal, having the same meaning as when they are said of creatures, for that would ignore the difference between God and creatures. On the other hand, neither are they equivocal, having no association to their creaturely meanings, for that would yield only meaninglessness. Instead they are analogical, opening through affirmation, negation, and excellence a perspective onto God, directing mind to God while not literally representing divine mysteries.”[24]

Johnson concurs that we use analogy:

“Analogy shapes every category of words used to speak about God. Metaphoric terms involve some form of concrete bodiliness as part of what they mean: God is a rock, a lion, a consuming fire.”[25]

We know when we speak thusly, we do not think God is actually a rock, or actually a lion, or actually a fire. Given that Johnson concedes this, we may question her reluctance to likewise accept using the analogy of male terms to speak about God.

Johnson appears to wish to speak for all women when she states:

“Women’s refusal of the exclusive claim of the white male symbol of the divine arises from the well-founded demand to adhere to the holy mystery of God, source of the blessing of their own existence, and to affirm their own intrinsic worth.”[26]

I find Johnson’s concentration on the refusal of women to accept the “white male symbol” to be overly broad and to fail to reflect that non-white symbols of God exist in cultures that are not primarily Anglo-Saxon. Sarah Jenkins’ piece, The Last Supper,[27] is reminiscent of Rembrandt’s work, but depicts Jesus and his Apostles as Blacks. Miracles are attributed to Mary as depicted in the Japanese carving known as Our Lady of Akita.[28]. In the Philippines, we find the Santo Niño de Cebú[29], a depiction of the Child Jesus which seems to be inspired by Buddha, and which is believed by Filipino Catholics to be miraculous. Our Lady of LaVang holds her child, a Vietnamese rendering of Jesus.[30] Father John Giuliani gives us a Native American version of the Transfiguration.[31] We may be most familiar with Christian art which overwhelmingly depicts God as male and Anglo-Saxon, but we would have to discount much of the world’s artwork, particularly contemporary art, to support Johnson’s statement of “the exclusive claim of the white male symbol of the divine.”

Johnson states that

“biblical tradition itself bears witness to the strong and consistent belief that God cannot be exhaustively known but even in revelation remains the mystery surrounding the world.”[32]

In support of this, she quotes Balthasar:

“the mystery of divine incomprehensibility burns more brightly here than anywhere.”[33]

I agree with both these statements. However, I do not agree that this supports Johnson’s position regarding the use of the female gender in speaking of God. She fails to show a connection between either of these statements and any benefit that may inure from calling God “she.” London’s review, paraphrasing Johnson, tells us

“Aquinas insists upon the deficiency of the female soul, mind, and will, her need to be governed by men and her corrupt role as temptress.”[34]

Aquinas does hold that

” As regards the individual nature, woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force or from some material indisposition, or even from some external influence; such as that of a south wind, which is moist, as the Philosopher observes (De Gener. Animal. iv, 2). On the other hand, as regards human nature in general, woman is not misbegotten, but is included in nature's intention as directed to the work of generation. Now the general intention of nature depends on God, Who is the universal Author of nature. Therefore, in producing nature, God formed not only the male but also the female.[35]”

I agree that Aquinas’ words here are rather harsh, but I am willing to concede that he is writing from his male point of view in a male-dominated society. However, I think Aquinas understood that God transcends the issue of male/female and would agree that using either “he” or “she” does not represent the fullness of God. Given his probable prejudice and his understanding of God as neither male nor female, he would likely disagree with Johnson’s desire to make God in the female image. Johnson herself quotes Aquinas:

“Now we cannot know what God is, but only what God is not; we must therefore consider the ways in which God does not exist, rather than the ways in which he does.”[36]

Aquinas might not have considered using feminine pronouns and imagery to consider God, but doing so might not contradict Aquinas’ teaching. However, I suggest that absent catechesis explaining that usage, the underlying reasons for such a change would become muddled. If, as Johnson suggests, women do not see themselves in male images of God, does adding female images than lessen men’s ability to see themselves? If society respects the male more than the female, would not female images of God tend to lessen one’s view of God? Do we change the words of the Our Father? If we promote images of the Holy Spirit as female, and say Mary is the spouse of the Holy Spirit, how do we then expect to have people understand why same-sex marriage is wrong? To move from millennia of referencing God with masculine terms to referencing God with feminine terms would be confusing, at best. It would appear to be a “politically correct” move rather than a theological one. I can only imagine the confusion of two competing images of God, one seen as male, the other as female.

Johnson argues that having solely male images of God denies full identification to women. The Church does suffer a loss by denying full identification to any group, but I disagree that the simple use of using male terms to refer to God excludes any group. If we were to apply Johnson’s position that by our depiction of God, we force any person to deny a portion of their own identity, we would need to depict God as simultaneously male, and female, and adult, and child, and Black, and Latino, and Filipino, and Chinese, and on and on. Yet we would still not be all-inclusive. If, as Johnson argues, we must see ourselves physically represented in images of God, how would she resolve God’s perfection in imagery for the blind, the lame, the deaf? In any attempt we could make to create an image of God that everyone identifies with equally, we would necessarily be molding God into our image, rather than recognizing that we are made in His.

I hope you’ve enjoyed today’s Theology on Tap. Stick around, the bar is open, but please don’t drink and drive. I do have a copy of each of the works of art I mentioned, so stop up and take a look. And mark your calendars for the next Theology on Tap. I’ll be discussing Islam’s affirmation that “there is no god but God” and responding to their critique of Christians for violating the unity of God by worshiping Jesus Christ as the Son of God. Thank you for coming!

Exhibit A

Sarah Jenkins, the Last Supper

Welcome to our continuing series of Theology on Tap. Today we are going to discuss Sister Elizabeth Johnson’s position on our male image of God, particularly as set forth in Chapter 6 of her1998 work, She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse.

Elizabeth Johnson, CSJ, a well-known contemporary feminist Catholic theologian, recently retired from her position as Distinguished Professor of Theology at my own alma mater, Fordham University, is not without controversy. She has been praised by the Jesuit priest James Martin, yet criticized by the USCCB’s Committee on Doctrine. That Committee, reviewing her work Quest for the Living God, stated

“Sr. Johnson claims to be retrieving fundamental insights from patristic and medieval theology. As we have seen, however, this is misleading, since under the guise of criticizing modern theism she criticizes crucial aspects of patristic and medieval theology, aspects that have become central elements of the Catholic theological tradition confirmed by magisterial teaching...”[1]

Father Martin counters that criticism, calling Johnson “one of [his] favorite theologians”[2] and calling She Who Is:

“a remarkable and remarkably readable work on the often overlooked feminine imagery of God in the Bible (and elsewhere in our tradition), which opened my mind to new ways of thinking about God.”[3]

Tonight, I want to discuss this work, which received such widely disparate reactions, particularly in the light of the writing of St. Thomas Aquinas’ view on images of God as set forth in his Summa Theologica.

Johnson holds that Judeo-Christian depictions of God, in both word and image, have been limited to the view of God as masculine and patriarchal. God is shown as Father, not mother; as Lord, not Lady; as King, not Queen. All of these words are gender specific. We may state that God is beyond gender, but that is not reflected in how we speak of God or in our imagery of God. In She Who Is,

“Johnson critiques traditional speech about God, which derives ‘almost exclusively from the world of ruling men,’ as oppressive.”[4]

Having grown up in the same pre-feminist era as Elizabeth Johnson, I understand her distaste for the exclusive use of male language and imagery for God, but I do not join her in viewing it as oppressive. I think the Bible leads us to this usage, and I think Aquinas would agree, as he reminds us:

“It is written (Exod 15:3): The Lord is a man of war. Almighty is his name.”[5]

In Exodus and other books of the Bible, God reveals Himself in masculine terms, and specifically as Father. A priest I know explains it like this:

If we refer to God as mother rather than father, we are manipulating God’s own words. If we claim God revealed Himself in the Bible as a Father due to patriarchal cultural conditioning, but is actually something different, then we are stating we cannot trust the words of the Bible. If we cannot trust the Bible, the inspired word of God, we would have to say that God is a liar. [6]

I doubt any of us want to go on record as calling God a liar.

Referring to God with male pronouns and terms is in keeping with God’s own word, and his role as Father. In Matthew 6:9, Jesus taught us to pray to God using these words:

“Pray then like this: Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.”[7]

Jesus could have said “our creator, or “our parent,” or even “our mother.” If we instead call God “mother” or, following Johnson’s lead, “Sophia,” we would seem to be molding our own interpretation of God rather than recognizing that of the Bible.

Yet, even though God calls himself Father, we must also recognize that as the Creator, He created without assistance. In nature, the vast majority of species requires participation of both male and female to procreate. We were all created in God’s image:

“When God created man, he made him in the likeness of God. Male and female he created them, and he blessed them and named them Man when they were created.”[8]

This translation, at least, delineates a difference between being “Man” and being “male and female.” Since God created Man in His own image, and since He created Man as both male and female, “Man” must include both masculine and feminine, and God Himself must include both those qualities which make one male and those qualities which make one female.

We must then ask if, because God presents himself as Father in the Bible, must we see Him specifically as male? In ST I, Q1, A10, Aquinas asks “Whether in Holy Scripture a Word May Have Several Senses?”[9] In his response, Aquinas states:

“The author of Holy Writ is God, in whose power it is to signify his meaning, not by words only (as man also can do), but also by things themselves. . .. Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. Xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses.”[10]

Aquinas makes further reference to the image of God:

“it is absolutely true that God is not a body;”[11]

“it is impossible that matter should exist in God,”[12] and

“God is the same as his essence or nature.”[13]

Aquinas holds that since God is not a body but a Spirit, God is neither male nor female, and would likely concur that the use of masculine imagery is due to a limitation of language, not of theology. While language does change over time, we have not yet moved to a genderless version of English. While we now consider “humankind” to be more appropriate than “mankind,” mankind is still understood to include both genders. Although we commonly use words once considered male-gendered for both genders, as in actor and author; some terms have transformed, like mail carrier for the older mailman; still other terms, like waiter and waitress, have thus far maintained a dual vocabulary. Referring to God with male pronouns and terms is a matter of convention. In language, we tacitly agree that a term which ordinarily or historically meant only males may include both male and female, where an alternative genderless word cannot be easily used. I believe Aquinas understands this limitation of language, and would thus not insist that we consider God as male because of the words of the Bible

Aquinas tells us that God is not just perfect, but most perfect.[14] If God is most perfect, and yet also male, would women then be less perfect than God? But, as I said earlier, Genesis delineates Man as both male and female. God is most perfect, perfectly perfect, and Man reflects God’s perfection. When God separated Man into male and female at the creation of Eve, He did not make Eve of a different substance than Adam, but of the same substance. If Adam and Eve are of the same substance, how could Eve be less than Adam? Admittedly, humans need both male and female to create new life, and God, who is neither male nor female, begat through His own power. We call Him God, because God relates to His creation as a Father, that is, paternalistically. The essence of Fatherhood is the begetting of life. God is the origin of all life, both human and divine, and therefore God is called Father. God begets life, and in the begetting of life, God's relationship to what he begets is as Father. We can state both that God is a Father because He begets, and that God begets because God is a Father.

Aquinas wrote

“God is in all things...as an agent present to that upon it works....it must be that God is in all things, and innermostly.”[15]

And, a little later,

“spiritual things contain those things in which they are; as the soul contains the body. Hence...all things are in God, inasmuch as they are contained by Him.”[16]

All things are in God. How, then, can God be simply male or female?

Aquinas also states:

“The blessed see the essence of God,”[17] and

“the essence of God, however, cannot be seen by any created similitude representing the divine essence itself as it really is.”[18]

If using male terms for God had a relation to the essence of God, it would follow that we would then see God as he is. But Aquinas is clear:

“it is impossible for any created intelligence to comprehend God”[19]

Aquinas tells us that God

“can be named by us from creatures, yet not so that the name which signified Him expressed the divine essence in itself.”[20]

Aquinas further states

“we attribute to Him abstract names to signify His simplicity, and concrete names to signify His substance and perfection, although both these kinds of names fail to express His mode of being, forasmuch as our intellect does not know Him in this life as He is.”

I think Aquinas would be quite comfortable referring to God with male-gendered words, but would insist that we consider God neither as male nor female. Once we claim gender in some way defines God, we are by our language than forcing a limit on our depiction of God.

We use words to speak of God, for words are a primary mode of communication. So, we refer to God with masculine imagery, and masculine titles, even though we know that God is neither male nor female. The characteristics of gender (masculine or feminine) are how God creates in His image in the created physical sphere. Created reality reflects the invisible reality. Mankind bears God's image in their Spirit because men and women can reason, love, will, choose, and know. Human beings are self-aware; animals are not.

Johnson’s distaste for using male imagery and pronouns to speak of God brings her to choose to use female imagery instead. In She Who Is,

“Johnson critiques traditional speech about God, which derives ‘almost exclusively from the world of ruling men,’ as oppressive.”[21]

She offers examples from other cultures:

“Johnson’s examination of classical theology points out the richness of both tradition and the Bible in the multitude of symbols used for God. There are symbols taken from personal relationships, from human crafts, from philosophy, and from nonliving objects such as rocks. Many terms refer to the work of creation. African usage tends to honor God as ‘The One who. . ..’ Islamic tradition has ninety-nine names for God; the hundredth name is thought to be the true one that does not exist because God is ineffable. Names multiply because none of them can express the whole nature of God.”[22]

Johnson has also written that:

“God is positively misrepresented if any one image is thought to be adequate.”[23]

For her, this means that we ought to have both male and female images of God. However, I hold that we have a multitude of images of God, that even the sum of all those images does not come close to the reality of God, and that bringing gender into the imagery has a negative, rather than a positive, effect on our understanding of God. We can neither see nor understand God and must thus understand our limitations. Both our words and our images for God are analogical. Johnson concedes this is taught by Aquinas:

“According to Aquinas, whose various uses of analogy have kept generations of commentators busy, this threefold movement of analogy is clarified by contrast with two other possibilities, On the one hand, words about God are not univocal, having the same meaning as when they are said of creatures, for that would ignore the difference between God and creatures. On the other hand, neither are they equivocal, having no association to their creaturely meanings, for that would yield only meaninglessness. Instead they are analogical, opening through affirmation, negation, and excellence a perspective onto God, directing mind to God while not literally representing divine mysteries.”[24]

Johnson concurs that we use analogy:

“Analogy shapes every category of words used to speak about God. Metaphoric terms involve some form of concrete bodiliness as part of what they mean: God is a rock, a lion, a consuming fire.”[25]

We know when we speak thusly, we do not think God is actually a rock, or actually a lion, or actually a fire. Given that Johnson concedes this, we may question her reluctance to likewise accept using the analogy of male terms to speak about God.

Johnson appears to wish to speak for all women when she states:

“Women’s refusal of the exclusive claim of the white male symbol of the divine arises from the well-founded demand to adhere to the holy mystery of God, source of the blessing of their own existence, and to affirm their own intrinsic worth.”[26]

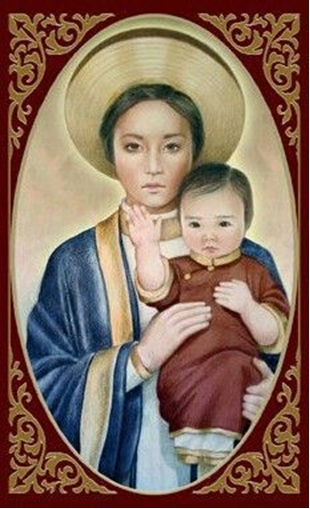

I find Johnson’s concentration on the refusal of women to accept the “white male symbol” to be overly broad and to fail to reflect that non-white symbols of God exist in cultures that are not primarily Anglo-Saxon. Sarah Jenkins’ piece, The Last Supper,[27] is reminiscent of Rembrandt’s work, but depicts Jesus and his Apostles as Blacks. Miracles are attributed to Mary as depicted in the Japanese carving known as Our Lady of Akita.[28]. In the Philippines, we find the Santo Niño de Cebú[29], a depiction of the Child Jesus which seems to be inspired by Buddha, and which is believed by Filipino Catholics to be miraculous. Our Lady of LaVang holds her child, a Vietnamese rendering of Jesus.[30] Father John Giuliani gives us a Native American version of the Transfiguration.[31] We may be most familiar with Christian art which overwhelmingly depicts God as male and Anglo-Saxon, but we would have to discount much of the world’s artwork, particularly contemporary art, to support Johnson’s statement of “the exclusive claim of the white male symbol of the divine.”

Johnson states that

“biblical tradition itself bears witness to the strong and consistent belief that God cannot be exhaustively known but even in revelation remains the mystery surrounding the world.”[32]

In support of this, she quotes Balthasar:

“the mystery of divine incomprehensibility burns more brightly here than anywhere.”[33]

I agree with both these statements. However, I do not agree that this supports Johnson’s position regarding the use of the female gender in speaking of God. She fails to show a connection between either of these statements and any benefit that may inure from calling God “she.” London’s review, paraphrasing Johnson, tells us

“Aquinas insists upon the deficiency of the female soul, mind, and will, her need to be governed by men and her corrupt role as temptress.”[34]

Aquinas does hold that

” As regards the individual nature, woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force or from some material indisposition, or even from some external influence; such as that of a south wind, which is moist, as the Philosopher observes (De Gener. Animal. iv, 2). On the other hand, as regards human nature in general, woman is not misbegotten, but is included in nature's intention as directed to the work of generation. Now the general intention of nature depends on God, Who is the universal Author of nature. Therefore, in producing nature, God formed not only the male but also the female.[35]”

I agree that Aquinas’ words here are rather harsh, but I am willing to concede that he is writing from his male point of view in a male-dominated society. However, I think Aquinas understood that God transcends the issue of male/female and would agree that using either “he” or “she” does not represent the fullness of God. Given his probable prejudice and his understanding of God as neither male nor female, he would likely disagree with Johnson’s desire to make God in the female image. Johnson herself quotes Aquinas:

“Now we cannot know what God is, but only what God is not; we must therefore consider the ways in which God does not exist, rather than the ways in which he does.”[36]

Aquinas might not have considered using feminine pronouns and imagery to consider God, but doing so might not contradict Aquinas’ teaching. However, I suggest that absent catechesis explaining that usage, the underlying reasons for such a change would become muddled. If, as Johnson suggests, women do not see themselves in male images of God, does adding female images than lessen men’s ability to see themselves? If society respects the male more than the female, would not female images of God tend to lessen one’s view of God? Do we change the words of the Our Father? If we promote images of the Holy Spirit as female, and say Mary is the spouse of the Holy Spirit, how do we then expect to have people understand why same-sex marriage is wrong? To move from millennia of referencing God with masculine terms to referencing God with feminine terms would be confusing, at best. It would appear to be a “politically correct” move rather than a theological one. I can only imagine the confusion of two competing images of God, one seen as male, the other as female.

Johnson argues that having solely male images of God denies full identification to women. The Church does suffer a loss by denying full identification to any group, but I disagree that the simple use of using male terms to refer to God excludes any group. If we were to apply Johnson’s position that by our depiction of God, we force any person to deny a portion of their own identity, we would need to depict God as simultaneously male, and female, and adult, and child, and Black, and Latino, and Filipino, and Chinese, and on and on. Yet we would still not be all-inclusive. If, as Johnson argues, we must see ourselves physically represented in images of God, how would she resolve God’s perfection in imagery for the blind, the lame, the deaf? In any attempt we could make to create an image of God that everyone identifies with equally, we would necessarily be molding God into our image, rather than recognizing that we are made in His.

I hope you’ve enjoyed today’s Theology on Tap. Stick around, the bar is open, but please don’t drink and drive. I do have a copy of each of the works of art I mentioned, so stop up and take a look. And mark your calendars for the next Theology on Tap. I’ll be discussing Islam’s affirmation that “there is no god but God” and responding to their critique of Christians for violating the unity of God by worshiping Jesus Christ as the Son of God. Thank you for coming!

Exhibit A

Sarah Jenkins, the Last Supper

Exhibit B

Our Lady of Akita

Exhibit C

Santo Niño de Cebú

Exhibit D

Our Lady of LaVang

Exhibit E

Father John Guiliani - Transfiguration

Bibliography

"A Message From Our Lady - Akita, Japan | EWTN". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 2020. https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/message-from-our-lady--akita-japan-5167.

Jenkins, Sarah. "The Last Supper By Sarah Jenkins (African American Art) | The Black Art Depot". Blackartdepot.Com, 2020. https://www.blackartdepot.com/products/the-last-supper-by-sarah-jenkins.

Johnson, C.S.J., Elizabeth. "THE INCOMPREHENSIBILITY OF GOD AND THE IMAGE OF GOD MALE AND FEMALE". Cdn.Theologicalstudies.Net, 1984. http://cdn.theologicalstudies.net/45/45.3/45.3.2.pdf.

Johnson, C.S.J., Elizabeth A. She Who Is: The Mystery Of God In Feminist Theological Discourse. New York: Crossroad, 1998.

London, Daniel. "She Who Is Sophia". Daniel Deforest London, 2011. https://deforestlondon.wordpress.com/2011/01/11/she-who-is-sophia-summary-of-the-mystery-of-god-in-feminist-theological-discourse/.

Martin, S.J., James. "The Case Of Sister Elizabeth Johnson". America Magazine, 2011. https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/case-sister-elizabeth-johnson.

"Native American Interpretation Of The Transfiguration Of Jesus". Curious Christian, 2020. https://curiouschristian.blog/2011/01/22/native-american-christian-art/.

"Santo Nino De Cebu - History". Santoninodecebu.Org, 2020. http://www.santoninodecebu.org/history.html.

The Holy Bible, Translated From The Original Tongues Being The First Version Set Forth A.D. 1611; Old And New Testaments Revised A.D. 1881-1885 And A.D. 1901. San Francisco, Calif.: Ignatius Press, 2006.

"The Shrine Of Our Lady Of La Vang". Asianews.It, 2020. http://www.asianews.it/news-en/The-shrine-of-Our-Lady-of-La-Vang-49100.html.

[1] James Martin, S.J., "The Case Of Sister Elizabeth Johnson", America Magazine, 2011, https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/case-sister-elizabeth-johnson.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid

[4] Daniel London, "She Who Is Sophia", 2. Daniel Deforest London, 2011, https://deforestlondon.wordpress.com/2011/01/11/she-who-is-sophia-summary-of-the-mystery-of-god-in-feminist-theological-discourse/.

[5] ST I, Q13, A 1Aquinas 122

[6] Private Correspondence, Father David Bechtel

[7] The Holy Bible, Translated From The Original Tongues Being The First Version Set Forth A.D. 1611; Old And New Testaments Revised A.D. 1881-1885 And A.D. 1901 (San Francisco, Calif.: Ignatius Press, 2006). Matthew 6:9

[8] Genesis 5:1-2

[9] ST I, Q1, A10, 14

[10] ST I, Q1, A10, 15

[11] ST I, Q3, A1, 26

[12] ST I, Q3, A2, 28

[13] ST I, Q3, A3. 29

[14] ST I, Q4, A1, 37

[15] ST I, Q8, A1, 67

[16] ST I, Q8, A1, 68

[17] ST 1, Q12, A1, 100

[18] ST I, Q12, A2, 102

[19] ST I, Q12, A7, 110

[20] ST I, Q13, A1, 122

[21] London, 2

[22] https://www.enotes.com/topics/she-who, Accessed Nov 6, 2020.

[23] Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., "THE INCOMPREHENSIBILITY OF GOD AND THE IMAGE OF GOD MALE AND FEMALE", Cdn.Theologicalstudies.Net, 1984, http://cdn.theologicalstudies.net/45/45.3/45.3.2.pdf., 452

[24] Elizabeth A Johnson, C.S.J., She Who Is: The Mystery Of God In Feminist Theological Discourse (New York: Crossroad, 1998). 113

[25] Ibid 114

[26] Ibid 117

[27] Exhibit A, Sarah Jenkins, "The Last Supper By Sarah Jenkins (African American Art) | The Black Art Depot", Blackartdepot.Com, 2020, https://www.blackartdepot.com/products/the-last-supper-by-sarah-jenkins.

[28] Exhibit B, "A Message From Our Lady - Akita, Japan | EWTN", EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 2020, https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/message-from-our-lady--akita-japan-5167.

[29] Exhibit C, "Santo Nino De Cebu - History", Santoninodecebu.Org, 2020, http://www.santoninodecebu.org/history.html.

[30] Exhibit D, "The Shrine Of Our Lady Of La Vang", Asianews.It, 2020, http://www.asianews.it/news-en/The-shrine-of-Our-Lady-of-La-Vang-49100.html.

[31] Exhibit E, "Native American Interpretation Of The Transfiguration Of Jesus", Curious Christian, 2020, https://curiouschristian.blog/2011/01/22/native-american-christian-art/.

[32] Johnson, She Who Is. 107

[33] Ibid 107; attributed to Balthasar, Unknown God, p 186

[34] London, 2

[35] ST I, Q92, A1, Reply to Objection 1

[36] Johnson, She Who Is, referencing ST I, Q3. 109

Exhibit A

Sarah Jenkins, the Last Supper

Exhibit B

Our Lady of Akita

Exhibit C

Santo Niño de Cebú

Exhibit D

Our Lady of LaVang

Exhibit E

Father John Guiliani - Transfiguration

Bibliography

"A Message From Our Lady - Akita, Japan | EWTN". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 2020. https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/message-from-our-lady--akita-japan-5167.

Jenkins, Sarah. "The Last Supper By Sarah Jenkins (African American Art) | The Black Art Depot". Blackartdepot.Com, 2020. https://www.blackartdepot.com/products/the-last-supper-by-sarah-jenkins.

Johnson, C.S.J., Elizabeth. "THE INCOMPREHENSIBILITY OF GOD AND THE IMAGE OF GOD MALE AND FEMALE". Cdn.Theologicalstudies.Net, 1984. http://cdn.theologicalstudies.net/45/45.3/45.3.2.pdf.

Johnson, C.S.J., Elizabeth A. She Who Is: The Mystery Of God In Feminist Theological Discourse. New York: Crossroad, 1998.

London, Daniel. "She Who Is Sophia". Daniel Deforest London, 2011. https://deforestlondon.wordpress.com/2011/01/11/she-who-is-sophia-summary-of-the-mystery-of-god-in-feminist-theological-discourse/.

Martin, S.J., James. "The Case Of Sister Elizabeth Johnson". America Magazine, 2011. https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/case-sister-elizabeth-johnson.

"Native American Interpretation Of The Transfiguration Of Jesus". Curious Christian, 2020. https://curiouschristian.blog/2011/01/22/native-american-christian-art/.

"Santo Nino De Cebu - History". Santoninodecebu.Org, 2020. http://www.santoninodecebu.org/history.html.

The Holy Bible, Translated From The Original Tongues Being The First Version Set Forth A.D. 1611; Old And New Testaments Revised A.D. 1881-1885 And A.D. 1901. San Francisco, Calif.: Ignatius Press, 2006.

"The Shrine Of Our Lady Of La Vang". Asianews.It, 2020. http://www.asianews.it/news-en/The-shrine-of-Our-Lady-of-La-Vang-49100.html.

Comments